Home |

About Us |

Membership |

Donate |

SCAMIT List |

Newsletters |

Tools |

Grants |

Documents |

Bight |

Links |

Contact Us |

![]()

International Polychaete Day — July 1, 2015

Commemorating the Life and Work of Kristian Fauchald

(1 July 1935 – 4 April 2015)

Remembrances

Fredrik Pleijel and Greg Rouse

Originally appearing at Marinespecies.org (WoRMS)

Kristian Fauchald, emeritus research zoologist at Smithsonian, and a founding editor of the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) passed away the 5th April 2015.

Contributed by Fredrik Pleijel (University of Gothenburg, Sweden) and Greg Rouse (Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UCSD, USA).

Kristian was born in Norway in 1935, took degrees at the University of Bergen, and in 1961 made his first publication on Norwegian occurrences of a crab; he thereafter published nearly exclusively on annelids for the rest of his career. He moved to California in 1965 for his Ph.D. studies with Olga Hartman and in 1969 was appointed assistant professor of biology at University of Southern California (USC). He was also appointed curator of marine annelids at the Allan Hancock Foundation, where he worked until 1979. The Allan Hancock Foundation had developed an outstanding polychaete collection under Olga Hartman and Kristian collaborated with her and carried on the tradition she had built as well as developing his own influential studies. While at USC and the Allan Hancock Foundation, Kristian’s publication highlights were his famous “Pink Book” guide to the polychaetes (Fauchald 1977) and the “Diet of Worms” together with Peter Jumars (Fauchald & Jumars 1979), the former cited 1005 and the latter 1737 times!

Kristian moved in 1979 to the Department of Invertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution where he remained. While there he concentrated on systematics within Eunicida resulting in a series of major revisionary monographs. In more recent times he has devoted his time to the problematic scaleworms. He was also instrumental in the first broadscale morphological cladistic analyses across annelids.

Beyond his own research Kristian was a mentor for many worm workers and he taught in a series of ‘Polychaete Biology Classes’ at Santa Catalina Marine Lab (with Paul C. Schroeder), Friday Harbor (with Peter Jumars, and later with Sally Woodin and Herb Wilson) and Biologisk Stasjon Espegrend, and in other polychaete-oriented courses at Ischia and Lecce in Italy, Brazil, Iceland and Madrid. The home of Kristian and his husband Leonard Hirsch in Washington DC was a haven to a long list of annelid workers.

Kristian was rare in many ways and, not least in keeping an open mind and being able to take part in a paradigm shift in systematics. Starting out with his first publication in 1961 he was well educated in the school of evolutionary taxonomy, but later, in the 1980s and 1990s re-educated himself into tree-thinking and phylogenetics. He had a life-long interest in philosophy of science and life itself.

A sense of the esteem with which he was held in the annelid community can be seen in the taxa that were named for him (including homonyms!) as compiled from WoRMS:

Amphisamytha fauchaldi Solís-Weiss & Hernández-Alcántara, 1994, Caulleryaspis fauchaldi Salazar-Vallejo & Buzhinskaja, 2013, Chirimia fauchaldi Light, 1991, Clavodorum fauchaldi Desbruyères, 1980, Clymenella fauchaldi Carrasco & Palma, 2003, Diopatra kristiani Paxton, 1998 Dodecaseta fauchaldi Green, 2002, Eunice kristiani Hartmann-Schröder & Zibrowius, 1998, Hypereteone fauchaldi (Kravitz & Jones, 1979), Eunice fauchaldi Miura, 1986, Fauchaldius Carrera-Parra & Salazar Vallejo, 1998, Fauchaldonuphis Paxton, 2005, Fauveliopsis fauchaldi Katzmann & Laubier, 1974, Gesaia fauchaldi Kirtley, 1994, Hypereteone fauchaldi (Kravitz & Jones, 1979), Kinbergonuphis fauchaldi Wu, Wang & Wu, 1987, Kinbergonuphis fauchaldi Lana, 1991, Kinbergonuphis kristiani Leon-Gonzalez, Rivera & Romero, 2004, Linopherus fauchaldi San Martín, 1986, Linopherus kristiani Salazar-Vallejo, 1987, Lumbrineris fauchaldi Blake, 1972, Marphysa fauchaldi Glasby & Hutchings, 2010, Melinna fauchaldi Gallardo, 1968, Neogyptis fauchaldi Pleijel, Rouse, Sundkvist & Nygren, 2012, Nereis fauchaldi Leon-Gonzalez & Diaz-Castaneda, 1998, Notodasus kristiani García-Garza, Hernandez-Valdez & De León-González, 2009, Paradiopatra fauchaldi Buzhinskaja, 1985, Piromis fauchaldi Salazar-Vallejo, 2011, Poecilochaetus fauchaldi Pilato & Cantone, 1976, Prionospio fauchaldi Maciolek, 1985, Pseudatherospio fauchaldi Lovell, 1994, Rullierinereis fauchaldi Leon-Gonzalez & Solis-Weiss, 2000, Sarsonuphis fauchaldi Kirkegaard, 1988 Sphaerephesia fauchaldi Kudenov, 1987, Sphaerodoridium fauchaldi Hartmann-Schröder, 1993 and Sphaero doropsis fauchaldi Hartmann-Schröder, 1979.

Kristian, or maestro as we called him behind his back, was a wonderful mentor for us both. He and Len hosted us in Washington DC as we began our wormy careers and we met many times over the succeeding years; in the field, at conferences and at courses. His deep knowledge of worms and philosophy constantly had us questioning and discussing, such as over a cold beer after a days work at the Smithsonian’s laboratory at Carrie Bow Cay, Belize.

He had a great laugh and we miss him.

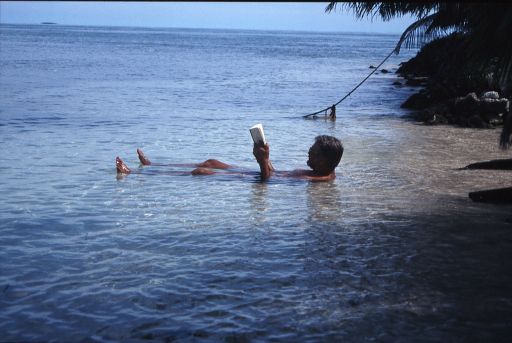

Image: Kristian on Carrie Bow Cay in 2006. The book is on Chinese philosophy.

His Early California History

Kristian’s father was a judge. Apparently the policy in Norway was to transfer the judges to different localities. His father was transferred to Tromso. I do not how old he was, but I believe that he had interest in biology and perhaps marine biology. He went to the Tromso museum often and there he met Dr. Soot-Ryen. Apparently Soot-Ryen played a role in Kristian’s early association with marine invertebrates and specifically polychaetes. Kristian published three papers on Norwegian fauna, including one on the family Nephtyidae, his first on polychaetes. In 1953 Soot-Ryen came to the Allan Hancock Foundation at USC to study and publish on bivalves. At the time I was going out on the Velero IV to take benthic samples for Olga Hartman. I met Soot-Ryen on one of the cruises to Catalina Island.

Around 1963-64, Kristian came to Los Angeles and visited the Allan Hancock Foundation for the first time. Obviously Soot-Ryen played a role in Kristian coming to California. I met Kristian at that time and brought him to CSULB where he presented a seminar on Norwegian biology. I do not know how long he remained at the Hancock Foundation on his first visit, but he apparently made the ground work to return and do his PhD under Dr Hartman. Kristian returned to Allan Hancock Foundation in 1965 and completed his PhD in 1969. He attended a party at my house in honor of Drs. Denise and Gerard Bellan who were working in my lab in July 1969.

Kristian and I both had a deeply admired Dr. Hartman and the two of us organized and edited the 1977 publication “Essays on Polychaetous Annelids in Memory of Dr. Olga Hartman” which contained articles by former students and polychaete workers from all over the world. Whenever we got together, including the last time in Australia in 2013, we shared stories about Dr. Hartman.

Karen Osborn and Linda Ward launched an initiative to establish International Polychaete Day on 1st of July to celebrate Kristian’s 80th birthday. This will take place in the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, where he spent his last 35 years as an active researcher. This is a magnificent idea that will help remember him and to encourage the interest for studying polychaetes. The wish is that a similar celebration be done as well in many other institutions and countries.

According to GoogleScholar as of mid-May, 2015, Kristian had two papers with over 1000 citations; one is the “Diet of Worms” a compilation of polychaetes’ feeding mechanisms, published with Peter Jumars (1757 citations), and the so-called Pink Book (1015 citations). The first one was selected as a CitationClassic when it had 245 citations and Kristian made an evaluation about it (Fauchald 1992); there, despite the fact of its usefulness and high citation rate, he concluded: “Many of our conclusions … are outdated. We were wrong, even spectacularly wrong sometimes.” A few years before (Fauchald 1989:748) he indicated that such synthesis “… was written as a summary of what little information was available in the 1970’s and was intended to spur investigations.” Just a few scientists dare to acknowledge their mistakes. Kristian was one of them; that was his intellectual stature.

Some members of our academic community have written an obituary already and listed the 36 taxa named after Kristian including two genera and 34 species (Pleijel & Rouse 2015). Further, as part of the celebration for his 70th birthday there was an special issue in a prestigious journal which included two relevant contributions; one was a tribute (Rouse et al. 2005), and the other was a compilation of his publications and the taxa he proposed or described including three families, 34 genera, and 256 species (Ward 2005).

For this eulogy I will combine some pleasant memories that changed my life, together with some details about his taxonomic philosophy which are apparently little understood or ignored. In both cases, I try to follow his path because Kristian did the same for one of his mentors: Carl Støp-Bowitz (Fauchald 2000). Kristian’s first publications were made with Hans Brattström, who was very influential in the development of marine biology in Chile as well (Bahamonde & Báez 2001), but it was Støp-Bowitz who offered some early guidance for his studies on polychaetes.

In 1979 Fernando Jiménez, a teacher in the Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Nuevo León, gave me an important recommendation: “You must seek a training period or intensive course with a polychaete specialist; otherwise, your progress will be very slow and limited.” I wrote to Marian Pettibone and to Kristian, who kindly suggested taking his polychaete summer course in Catalina Island. I arrived with a few ideas from invertebrate zoology textbooks but no practical experience with the polychaetes; I had a lab cloth and a rudimentary small forceps and one dissecting needle, but nothing else.

The course had two sections. The first two weeks there were two lectures and the remaining three weeks, we were supposed to work in our research project. Lectures were following the corresponding section by Pierre Fauvel in the Traité de Zoologie, and I was lucky I coud read French as well as English, albeit my spoken English was terrible.

Lab sessions were very useful for me because I got used to terminology and keys in the Pink Book, and learnt about polychaete’s morphology. I became too confident, too soon, because when I was unable to identify a lumbrinerid, I said aloud “Kristian, it seems that your key to genera of lumbrinerids is defective, because I cannot arrive to any genus with this worm.” Kristian said: “That’s interesting; let me take a look at it.” He sat at my scope and said: “You’re looking at the worm’s posterior end; the key is for anterior regions.”

I did learn as much as possible and enjoyed his guidance and patience with my frequent mistakes. If I tell that the course changed my life, that is to say very little, because I had no academic life before; I returned to Mexico full of enthusiasm and willing to make an academic career by studying polychaetes. This is why I owe Kristian most I have done on polychaetes; I was lucky enough to acknowledge this in public during his retirement party. Thanks again, Kristian.

By the way, Kristian recommended to focus on one or a few families such that I could have a deep understanding of the group; my reply and approach was the opposite because I felt that it was better to follow his achievement on Panamian polychaetes (Fauchald 1977), because he had dealt with all families.

I was wrong because I only grasp a shallow knowledge about the group; however, these mistakes had a positive effect because I could encourage some young colleagues that, like Ángel de León and Gerardo Góngora, managed to concentrate in a single family for their start, and one decade after we made the White Book of the Mexican polychaetes.

I was also lucky by meeting with Kristian more or less frequently, mostly in Washington but he visited Chetumal twice. During my sabbatical leave I was living with Len and him for three months, and this time allowed me to understand better why there was no simple questions regarding polychaete taxonomy: his replies were always pointing towards a research problem that deserved some attention, even if it seemed too distant from the current topic. Kristian made this not to overwhelm me, or others, but because by doing so, he emphasized the need to widen our own perspective and to improve our understanding of current research topics.

According to Wikipedia, “in philosophy, Eclectics use elements from multiple philosophies, texts, life experiences and their own philosophical ideas.” On this ground, it is surprising that Kristian’s synthesis about philosophy of biology and the study of polychaetes (Fauchald 1989) has only 3 citations after GoogleScholar. His conclusions, and the need to improve the current scenario are far from being outdated. The main points are: a) most publications are descriptions of single or few species and type materials are rarely examined, b) most taxonomic groups have not been revised, and c) benthic ecological sampling is done with ill-defined objectives, and identifications of polychaetes are often wrong whenever done in a hurry.

Taxonomy entered the public and political agenda after the social concern about biodiversity’s future. There were some specific, wishful recommendations and the Darwin Initiative and the NSF’s PEET (Partnership for Enhancing Expertise in Taxonomy) programs were launched; however, the results fall behind expectations because funding was modest and some of the trainees failed to find a position as taxonomists (Agnarsson & Kuntner 2007, Rodman 2007).

Beyond funding availability for new positions, there is a series of desirable practices for improving taxonomic studies of marine biodiversity; Kristian was involved in a series of considerations regarding the impact of fisheries (Vecchione et al. 2000), along two main issues: identifications and reliability. Among factors affecting the quality of identifications are the sources of information, the experience of identifiers, the difficulty for detecting some diagnostic features, ontogenetic changes, preservation quality of specimens, and presence of similar species. Some reasons for being suspicious include anomalous distributions, lack of reference or voucher materials, and improbable environmental conditions, what we have regarded as ecological horizon elsewhere (Salazar-Vallejo et al. 2014), for emphasizing that species could be present in similar conditions of temperature, salinity, substrate and depth.

Kristian also dealt with the taxonomic impediment (Fauchald 2003). This implies the contrast bordering the need of information for bioconservation purposes, the high rate of landscape transformation, and the depressing condition of taxonomy. Thus, taxonomic impediment is due to the lack of taxonomic information, the many missing pieces of information, and the lack of adequate training programs in taxonomy. In this contribution Kristian gave some examples happening in the Smithsonian and emphasized the need for generating identification keys, taxonomic revisions, and phylogenetic analysis, together with a need to improve the quality of new species descriptions.

This is a pending challenge. One hopes we can manage to follow his recommendations as the best means to honor his legacy and try to emulate his efforts.

References

Agnarsson I & Kuntner M 2007 Taxonomy in a changing world: Seeking solutions for a Science in crisis. Systematic Biology 56:531–539.

Bahamonde N & Báez P 2001 Hans Brattstrøm (1908–2000). Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía 36:123–127.

Fauchald K 1977 Polychaetes from intertidal areas in Panama, with a review of previous shallow-water records. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 221:1–81.

Fauchald K 1989 The second annual Riser Lecture: Eclecticism and the study of polychaetes. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 102:742–752.

Fauchald K 1992 Diet of worms. Current Contents 40(5 Oct.):8.

Fauchald K 2000 Carl Støp-Bowitz (1914–1997). Bulletin of Marine Science 67:10.

Fauchald K 2003 Taxonomic impediment in the study of marine invertebrates; pp 637–642 In The New Panorama of Animal Evolution. Legakis A, Sfenthouakis S, Polymeni R & Thessalou-Legaski M (eds), Proceedings of the 18th International Congress of Zoology. Pensoft Publishers, Moscow (http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/15956044).

Pleijel F & Rouse G 2015 Obituary — Kristian Fauchald: WoRMS Polychaeta founding editor. http://www.marinespecies.org/news.php?p=show&id=4152.

Rodman JE 2007 Reflections on PEET, the Partnerships for Enhancing Expertise in Taxonomy. Zootaxa 1668:41–46.

Rouse G, Gambi MC & Levin LA 2005 Kristian Fauchald: A tribute. Marine Ecology 26:141-144.

Salazar-Vallejo SI, Carrera-Parra LF, González NE & Salazar-González SA 2014 Biota portuaria y taxonomía; pp 33-54 In Especies Invasoras Acuáticas: Casos de Estudio en Ecosistemas de México. AM Low-Pfeng, PA Quijón & EM Peters-Recagno (eds). SEMARNAT, INECC & Univ. Prince Edward Island, México, 643 pp (www2.inecc.gob.mx/publicaciones/consultaPublicacion.html?id_pub=713).

Vecchione M, Mickevich MF, Fauchald K, Collette BB, Williams AB, Munroe TA & Young RE 2000 Importance of assessing taxonomic adequacy in determining fishing effects on marine biodiversity. ICES Journal of Marine Science 57:677–681.

Ward L 2005 The publications of Kristian Fauchald and the polychaete taxa named in those works. Marine Ecology 26:145–154.

(Sergio I. Salazar-Vallejo, ECOSUR-Chetumal, México)

On Kristian Fauchald: A Personal Retrospective

Kirk Fitzhugh, Ph.D.

Curator of Polychaetes

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County 900 Exposition Blvd, Los Angeles CA 90007

Perhaps what comes to mind for most people when thinking of Kristian Fauchald are his many contributions to the study of polychaetous annelids. Having known Kristian for 33 years, from my days as a master’s student to having him as my PhD advisor and subsequently as a colleague, I think of Kristian in a different light: he was a person who had an immense love of the process of scientific inquiry. Polychaetes were the vehicle Kristian used for that pursuit of the greater glory that is our inquisitive nature, our desire to gain understanding — the very qualities that make science a life worth living. Indeed, the scope of Kristian’s ambitions is evident in a letter dated October 1964 to his future PhD mentor, Dr. Olga Hartman. Twenty-nine year old Kristian informs Dr. Hartman of his work at the Marine Biological Station at Espeland, Norway, and his greater aspirations: “As you know I have now got a position here,… which means that I can sit down, without doing anything except my official work for the station the rest of my life. I do not think it is a very satisfying idea, I want to learn as much as possible and do as much as possible, and this is not the place for that.” That desire for experiencing more led to Kristian moving to Los Angeles in 1965 to begin his PhD at the University of Southern California with Dr. Hartman.

Kristian loved sharing his passion for science with anyone he felt understood the beauty of science and was consumed by inquiry. And it was my own insatiable inquisitiveness about nature, and a healthy dose of obsession with polychaetes, that resulted in the start of my relationship with Kristian as my PhD mentor in the autumn of 1983. And while it was a relationship that began with the topics of polychaetes and marine ecology, it was not long until Kristian most subtlety handed me what I call an ‘intellectual oar’ for the metaphorical boat that would become my intellectual journey into science for the rest of my life. That ‘oar’ came at the end of a brief conversation, as a suggestion that I pursue philosophy of science as the framework for my more applied interests in polychaetes. Little did I know of the effect that off-the- cuff suggestion would have on me. But that was the beauty of communicating with Kristian. He never told me what I should do; he left that for me to decide. He merely offered one of the oars for the trip.

I made many a mistake on my journey, and will continue to do so, but I have tried to treat each as part of learning that would help me steer a more productive path. Uncertainty. Fallibility. Always be prepared to be wrong, because you will be. Those were the mottoes Kristian continually emphasized, and I loved it. He showed me that it is alright to be wrong, for to admit to mistakes means you're doing science correctly. Kristian loved critical discourse, and we would daily sit in his office, or he would wander down to the office I occupied, to chew over some concept, or we would skewer something we read in a journal article. Kristian provided the atmosphere of discourse like I've never encountered with any other. I always felt he abhorred the status quo when it came to polychaete systematics, because that's just not how science should be done.

I've said little about Kristian and polychaetes because we talked less about worms and more about the nature of science, the nature of observation, and the nuances of evolution. And those topics fueled my intellectual evolution and critical attitude. At every turn, Kristian fed me perspectives that I never before considered, and every consequence brought with it the exciting feeling that my grasp on science and a way of seeing the world were expanding. Polychaetes became just a vehicle to learn philosophy of science and to apply that to systematics overall. More fuel for the discussions with Kristian. It was as if we created a feedback loop that enhanced our mutual intellectual growth, and it was all due to that ‘intellectual oar’ Kristian offered me several years prior. Years later, it was the consequences of my interactions with Kristian that led me to forsake much of what is done in my own field of research, for the atmosphere of certainty, uncritical thinking, and disdain for the philosophical principles upon which reasoning in science are obliged to follow have become the norm in systematics. Exactly the state of affairs Kristian showed me to be wrong for a scientist, and what I confirmed in my subsequent 20+ years of constantly stepping outside of polychaetes and into the waters of philosophy. And while I've received strong criticism from colleagues for both my choice of direction and the ideas that I have put forward, I have no regrets, because my goal has been to emulate the best qualities Kristian possessed: a love of pursuing and communicating science. That ‘intellectual oar’ he offered me in 1983 was the right one, because it was the same as he used on his own intellectual journey. For that I will be eternally grateful.

Thank you, Kristian.

Taxa named by and for Kristian Fauchald

Curatorships

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County — Polychaetous Annelids

National Museum of Natural History (Smithsonian) — Department of Invertebrate Zoology

Kristian in Southern California

Dave Young and Kristian Fauchald at USC’s Catalina Lab.

Russ Zimmer and Kristian Fauchald circa 1977.

Kristian Fauchald at SCAMIT in May 1988.

Kristian Fauchald at SCAMIT in May 2006.

NEP species named in honor of Kristian Fauchauld

Caulleryaspis fauchalidi Salazar-Vallejo & Buzhinskaja 2013

Hypereteone fauchalidi (Kravitz & Jones 2979)

Nereis fauchaldi Leon-Gonzalez & Diaz-Castaneda 1998

Pseudathrospio fauchaldi

Lovell 1994

Polychaete images by Leslie Harris

All images below are copyright © by Leslie Harris

Leslie Harris.jpg)

Amaeana sp A

Leslie Harris.jpg)

Amblyosyllis speciosa fig D of Imajima

Leslie Harris.jpg)

Amblyosyllis speciosa sensu Dorsey

Amphitritinae sp 1

Aonides oxycephala

Arabella semimaculata

Arctonoe on Parastichopus parvimensis

Leslie Harris.jpg)

Boccardia claparedei and B. proboscidea

.jpg)

Cheilonereis cyclurus

Collage for LACM Naturalist

Dorvilleidae

Leslie Harris.jpg)

Epigamia noroi

Eulalia californiensis

Eunice

Eunice antennata

Harmothoe imbricata group

Hediste limnicola

Hobsonia floridana and Nematostella vectensis

Hydroides ezoensis

Lanicides

Malmgreniella variegata

Manayunkia

Marenzelleria viridis

Marenzelleria viridis

Myrianida pachycera

Neanthes succinea

Neanthes succinea

Neanthes succinea

Nereid epitoke

Nereiphylla

Leslie Harris.jpg)

Nicolea sp A

Notaulax occidentalis

Notopygos caribea

Ophiodromus pugettensis

Orbinid

Petaloproctus

Phyllodoce medipapillata

Leslie Harris.jpg)

Proceraea okadai

Sabaco elongata

Streblospio benedicti

Streblospio benedicti

Copyright © SCAMIT. All Rights Reserved. |

|